Kathleen Cockroft shares her life story, including the loss of her husband Roy during the Korean War. She was eight months pregnant with their child when he was killed. Kathleen describes growing up in the Huddersfield area of West Yorkshire during the inter-war years. She recalls meeting her husband, courting, and their frugal wedding in 1951. Kathleen recounts her treatment as a young widow and mother and talks about her second marriage, her pilgrimage to Korea, and her recent efforts to have her first husband’s name commemorated locally. The interview was conducted by Nadine Muller on 13 November 2018.

Click here to download the transcript of this interview as a pdf file.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

Kath, can you just confirm your full name for me?

The name I am now, not the previous name?

Whichever you prefer.

It’s Kathleen Cockcroft, and I’m known as Kath most of the time, but my husband always called me Kathleen.

Can you tell me the year you were born?

I was born in 1931.

Thank you very much. Kathleen, can we start with where you grew up? Tell me something about your childhood. What was that like? What was your family like?

I was one of six. My father had been widowed after the birth of the third child. He was on his own for I think around about three years before he met my mother. They got married and she brought his children up plus three girls with him. So we all had the same surname so there was no problem of half sisters. One boy and five girls, and I was the … next to the youngest.

Where was that?

He was born … Both my parents were born in Beverley, and so I have connections with Beverley. I was christened there and one or two of my sisters were. And then he moved eventually to Huddersfield, and I was born at Almondbury. And so about six days after I was born, I must have been a special person, because there was an earthquake and I was thrown, so mother said, from one side of the cot to the other. And I think that was about the 6th of June. So I must have arrived and made myself known. So I was born at Almondbury, and then we moved further down, more towards Huddersfield, and father was buying a property down there where we were raised. And I was … went to school from there. So …

What did your dad do?

He’d been … he worked his way up from being a bus driver to an inspector and then he went into, what did they used to call it? Where you … National Insurance? No, was it National Insurance where you paid so much a week for you to have a pension? He was a civil servant. And we were going to go and live in London when the war was on at Walthamstow but he started with heart problems so that ruled that out. But he was in the Home Guard. So …

What was it like being one of six? What was your childhood like?

It was never quiet. [Laughs] And, and … the war years, food was short, so you had to make do and do without. But there was always plenty going off, so you always had somebody to play with and that, but you had to share everything. So, we survived. We never felt deprived. Didn’t do well at school because it was the war years and there weren’t the facilities to, to do anything. But I didn’t particularly like school. [Laughs] I’m not academic.

How come?

Ha! I wasn’t given the proper brains. [Laughs] But all in all, yes, we had a happy childhood, yes.

What did you get up to? What would a normal day look like with six of you?

I don’t really know. I suppose you helped around the house, didn’t you? But yet, you played out a lot and you only went home when you were hungry. [Laughs] So, there was … We played games with the neighbours’ children and things like that, and we were all taught to swim. So swimming played a big part in my childhood. I used to swim with two sisters and we swam as a team. And we used to win. [Laughs] So … But we didn’t have a car so we didn’t keep in contact with grandparents because they lived in Beverley and, you know, there was not enough money to take six children round. But my brother, who was the eldest, he joined the Air Force when he was 16. And he would only come home on leave. So really, I haven’t got a lot of memories of him – him living with us.

So what were things like when you were growing up as a teenager? When did you first meet your first husband? Do you remember when you first met him?

I met him at a youth club actually, yes. Um, but teenage years were very frugal because rationing was on, and you had coupons for sweets and coupons for clothing, so you ‘made do’ with what you’d got. I think I’d be about 17, I think, when I met my future husband at the youth club. And he was into sport. He played football. And then he was – he’d taken basketball up, which he was very good at. And he was learning to wrestle. So we went to the pictures quite often, which was a lot cheaper than now. And they used to have two – two films on a week. So you get – and a lot of cinemas. There was a cinema in every district. So … Yes, we didn’t feel deprived, you just got on with what you’d got. So …

Do you remember the first time you spoke to him?

Oh no. No.

Or your first date?

Not really. Well, I know that he played football and we’d only just met, and he’d said where they were going to play, and I’d made a point of saying I’d go to watch. He had broken his leg and he sort of made his way, under great difficulties, because he said he’d see me. I think he was frightened that if he didn’t turn up, he would be history. [Laughs] But he was a kind boy.

How did things go from there? So you used to go to the pictures a lot?

Yes, we went to the pictures a lot and walking. Yes, and … I’m just wondering when I foolishly bought a little Scottie puppy that was quite a handful so we’d take the dog a walk, wouldn’t we? So, it’s a long time ago, 65 years since he died so you’re talking going on for nearly 70 years ago. But you left school at 14 in those days and I had various jobs and then your friends are earning more than you are so I went into a mill as a weaver. And he left school and got a job as a trainee upholsterer. And, he loved his job. And so, in those days you could either finish your apprenticeship, and then do your national service, or you could do your National Service and then go back to being an apprentice. He chose to finish it. So when he finished his apprenticeship, and they were seven-year apprenticeships, when he was 21 – this was after we were married – he became eligible. So, in the August he was taken away to do his National Service. So … Do you want me to say anything else?

Whatever you want to share with us. What was your wedding like?

Very frugal actually, because we weren’t earning big money and war was on so people gave me their coupons to go and get an outfit. It wasn’t a white dress. It was a very nice dress. I think it was a greyish blue. It had a little hat. And we got married in church. And unfortunately we couldn’t afford the organ, so it was ‘clip, clop, clip, clop’ with my heels all the way down on my father’s arm. So … Then we came out and you just went somewhere local which was opposite the church and had a ham tea with trifle, things like that and a cake. Couldn’t afford a honeymoon. [Laughs] So, yes. But then we weren’t married long then when he was called. We were living in a one up and one down.

When was this? When did you get married, Kathleen?

November 1951. And so he was called up in 1952. Went in to do his National Service. He chose the Army because he said the Air Force was three years and he would be out quicker, in two. So he went in the Army and went to Richmond into the Green Howards and did his ‘square bashing.’ And then he did the Passing out Parade, which I went to by myself. Then we – he came out and before you knew what was happening, he was in the Duke of Wellingtons then. He’d come home on leave prior to being, what was the word for it, vacation. And he went on this boat and that’s where he learnt to fight. I’d never heard of Korea, didn’t know where Korea was but we were fighting with the United Nations. And he was taught to fight, so I was told, on the boat going over because all they’d done at Richmond was square bashing, “Do as your told, you’re in the Army.”

So unfortunately, letters went backwards and forwards, heavily censored. They didn’t go with phones like they do nowadays when they join the Army and they keep in touch. You were lucky to get a letter, and you were – half of it had been blacked out. And the next I knew, I found out I was pregnant. It must have happened when I went to the Passing-Out Parade. And, so he knew I was having a baby but we didn’t know the sex in those days. And, I chose the first name which was Robert and he chose the second name which was Gary. And I gave birth after he’d been killed. I was eight months pregnant. And unfortunately, at seven months, I lost my father. He died. My mother and I were widowed within a month of each other. So he was … I was eight months pregnant, and then I had a healthy baby boy. So.

Did you write to your husband to let him know you were pregnant?

Oh yes. That, that’s why he’d chosen the second name, you see. We talked about what we would do when he came back and, you know, things like that.

What were the plans? Do you remember what you wrote about?

No, not after 65 or more years, no. No, I mean we were in this one up and one down, very basic, second-hand furniture, nothing like they have now. No televisions, no nothing. And you were just glad that you weren’t living with your parents, sort of thing. And then when that happened, times were hard you see. Money was short and I went back to live at home but my mother, due to circumstances, had to move into something smaller so I moved in with her, into the family house to start with. And then into this, basically, one up and one down. My sister was living at home as well but it was a dreadful time because they didn’t tell you, in those days, like they do now. Do you want me to say what happened or not?

If you’d like to.

Well I was eight months pregnant and very pleased that I was pregnant, even though it was unexpected and I was sat knitting in the front garden. We didn’t have a back garden because it was like a back to back but it was a huge house. And, I was sat knitting baby clothes when this car pulled up outside and these two policemen got out and looked at me because I was eight months pregnant, said, “Is your dad in?” and I had to say, “My father has died but my mother is in,” so they went and rang the bell. I thought they looked at me strange when they came back out after a few minutes and then my mother said – came to the door and said that, “I think you should come in, I’ve got something to tell you.” And it was just a piece of paper that said that they were sorry to say that he’d been killed in Korea. And that was the 24th May which was a spring bank … they used to call it Whit Sunday. And she broke the news to me that Roy had been killed but you can’t come to terms when there’s no body. So I was eight months pregnant, so it wasn’t a nice period that, no.

And the policemen told your mother rather than…?

Yes, break it to me myself. But they have some dreadful jobs to do, haven’t they? I felt so sorry for them, but obviously they could see I was pregnant as well. So ah – there was no word from anybody else official, or “Are you alright? Do you need anything?” You’re just on your own. And of course, I ended up going to hospital for a check-up, a normal one, and be kept in because I’d gone – my blood pressure was sky high. And it was no different in those days to what it is now. There were few beds so I was booted out. I was sat waiting for my mother because there were no cars or anything in those days, my mother coming to fetch me home. I was sat in a chair waiting for my mother coming and a lady nursing a baby in the bed I’d just vacated. So times were hard because, I think I got £6 a week to live on. That was for me and the baby.

Was that your husband’s pension?

No, a war pension. I mean it was a pittance and after a few weeks I did arrange to see someone and it was a room full of men sat round a table. They took one look at me and they said, “How old are you? Oh, you’re young enough to get married again. You need to go to work. You can go to work.” I had a six week old baby and I was told to go to work. And I went to work. And I said, I never got any extra money. They said I had to earn it. And I did go, I think my baby was about five months old and I said I would never ask for another ha’penny if I starved. So, you weren’t given – I mean he’s buried abroad. I wouldn’t want him bringing back if they said they were bringing them all back, I wouldn’t want that. But nobody did any follow up to see if you were alright or anything. So I did go to work and I decided that my little boy was a handful for my mother. I was a lot older than that when I was looking after my great grandchildren. But I’d got him in a nursery and I used to go on four buses to work after I’d dropped him off, two buses to drop him off, two buses to get to work, and then in the afternoon, four buses home. So …

Then it didn’t work out living with my mother because, you like to be on your own so I put my name down for a council house. And I got a prefab. And, they were very well designed, but they were bitterly cold in winter and roasting hot in summer. But I did go to work and my son was four when I remarried. My husband brought my child up. ‘Cause he was so excited because the nurses at the nursery said to me, “Are you getting married again? Your little boy has said, ‘I’m having a new daddy.” [Laughs] So, it was lovely to stay at home and look after him. It was not – it was hard, yes, very hard.

So did you get the war widow’s pension?

£6 a week.

Did you have to apply for that?

Oh no. But when you remarried in those days, if you were living with anyone, they stopped your pension. And if you remarried, you had to inform them and they stopped your pension but they kept on, it was something like £2.50 a week for my child. My husband never actually adopted him, but he brought him up. So, the pension stopped when I remarried. But it certainly isn’t like it is now, but we won’t go into that because I don’t want to sound bitter.

What did you feel like when your war widow’s pension was stopped? Did you feel that was…?

No, it was just the way things were. You know, you never questioned anything in those days, no. It was just one of those things. My husband wasn’t a big earner but at least we had a wage coming in every week. And then – we, we managed. You didn’t have such high things to aim for. You more or less just lived every day as it came and you holidayed at the nearest resort instead of flying off somewhere like they do now and hoped it didn’t rain. [Laughs] But I think what hurt about being widowed was when I went to the park with, with him in the pram and the daddies were playing with the children, that, that did hurt. But I always said I wasn’t the first and I wouldn’t be the last to be widowed and it’s still happening. Yes. But I was, for years, upset that he’d given his life for his country. But, it still rankled that it was National Service he was doing. He didn’t want to go in the Army and be a soldier. And, and that is what hurt most.

But it, it also hurt that there was nowhere local. I mean we have a lovely park, Greenhead Park. It has a lovely memorial area flagged with pillars up and there isn’t one person’s name there that has died for the country there. And there was nowhere that had his name. He just didn’t exist. So for years I kept asking people, British Legion and other people. No, they couldn’t do anything. Then unfortunately, my husband had had a bad stroke and went into a nursing home. And I felt awful doing it, but I was 82 and I – it still rankled that my husband had given his life and nowhere was his name in Huddersfield. So I went and knocked on the vicar’s door of the church where my husband had grown, got up and gone to school, and they went from the school to the church for services. And there was this very nice lady who was in the middle of bathing child, a baby, came down and talked to me. She put the wheels in motion of having his name at the church.

So after – and a councillor called Terry White, he did a lot to help me. He took over and the British Legion, at last, took notice but it was me that knocked on the door and said, “My husband has given his life for his country, this is the church where he went to, and I would like his name.” So I was instrumental but Mr – Terry, Terry was the one that did everything that needed doing. He found out – the church insisted it was a certain wood, so we’ve got this plaque about that big with his name on, his age, you know, his company. He was the Duke of Wellingtons then. And after, what will it be now, Peter was in that home, he’s been dead nearly four years. It would be five years or more. I felt awful doing it when my second husband was in a nursing home but at 82, if I hadn’t have done it, it wasn’t going to get done. So it was a lovely service when they dedicated it. The British Legion came with the flags, with the brass band belonging to Meltham. They came and marched through the streets. And his name is in the church, and that is what I wanted.

I’ve been to the Arboretum and that is a beautiful place, I’d love to go again. I saw his name and it was there. So… And, it’s a lovely place because – I don’t know whether you’ve been or not, they’re not captains, they’re not colonels, they’re not sergeants, they’re all the same. They’re human beings. And there was his name up with everybody else’s. It’s in … in the days they died, each one, you know. That’s how they do it. But what upset me was the amount of space they’d left for future deaths and already there’s another couple of columns got added names. But it’s a beautiful place. It was very moving when we went there.

The Armed Forces Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum (Alrewas).

What was the occasion? Who did you go with to the Arboretum?

It didn’t work out that. My son said he’d take me, but he was dragging his heels so to speak. My son-in-law that lives in Surrey, with his wife, they arranged for us to go. They drove up from Surrey. We drove down, I did, from here and we met up. And we stayed overnight somewhere, and we went and … We hadn’t long enough really, but it’s been one of the most moving experiences, I think. But I did actually see his name. It’s a beautiful place. It’s a very small thing for Korea. You probably didn’t pick any … Did you go to see anything special when you went?

No, we just had a general look round and there’s the War Widows’ Rose Garden.

Hmmm. Because there’s, like … babies. You name it, they’re there. They’ve added to it since we went. Erm, so, I’d wanted to go and Ian made it, made it happen, yes. So at last things sort of had their loose ends tied up so to speak.

Did it feel like some sort of closure for you once his name was…?

Oh yes, yes, yes, yes, yeah. Yeah ‘cause … Ian took a lot of photographs. I’ve got a black bag with things to do with Korea, and Roy, and a letter from someone that, I think they’d served there and very kindly looked Roy’s history up and found out how he was killed and wrote and told me about his last few hours, which was a comfort. But it was a dreadful war because … It’s a dreadful place to fight and our boys were going out inadequately dressed. They were having like summer – this is what I was told, I only know hearsay – that it was the Americans that rescued them from starving while they were fighting and practically clothed them in thicker clothing than they went out with. So [sighs], it’s a different game now.

Kathleen, can I take you back to when your son was little and you said you had to go to work, what kind of job did you do?

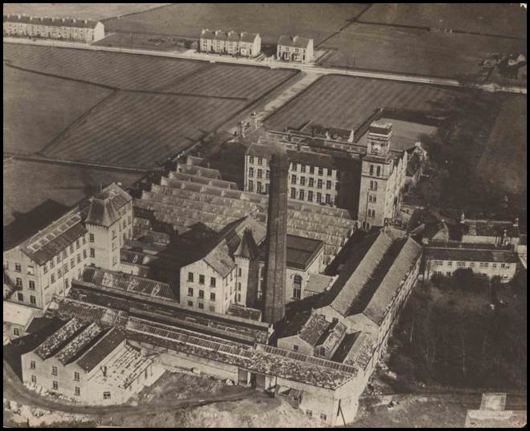

I was a weave, you see, I’d trained to be a weaver and so they were very kind. It was a mill at Newsome that isn’t there. The mill is there, but it’s been … Arson. It’s has fire set to it. They don’t know what to do with it. But they allowed me to work, to get there when I could after I’d gone on these four buses. And when he was poorly I just took the time off and that. So, they were very considerate to me, my circumstances, yes. Didn’t earn a lot because when you’re a weaver, if your loom breaks down your wage stops. They had tuners that, you used to have to go and ask the tuner if he would come and have a look at your loom and get it going again. You were paid on what you produced, so to speak. I did what they said. I went out to work. But I never owed anybody any money. I paid for everything that we ate and my rent. I paid my rent. Oh dear.

Newsome Mills, Huddersfield.

When did you tell your son what had happened to his …?

I can’t really remember. I mean he … His parents were very good to me, and when I remarried, they gave me their blessing. And my son used to go and spend Saturdays with them. I don’t think … It was just one of those things, you just got on with life. You didn’t sit down and say, “You’ve lost your father,” or, or anything like that. As far as he was concerned, he’d had a mum and a dad. And, it wasn’t something that … It was something that had happened in the past and I was just existing the best way I could. So, I really can’t give you an honest answer for that ‘cause there isn’t one, you know? I mean he had a lovely photo of his dad. I don’t know whether he’s got it on the wall now or not. But it’s strange because when they’ve never known a person. He would have had such a different bringing up with my first husband who was physically active in sport. My second husband liked nothing better than gardening, pottering around, building walls, creating gardens, his greenhouse, his hut. Ah, he was very good. I mean there’s the marquetry picture up there. He made a lot of marquetry pictures which take a lot of doing. He was very skilled. He … lovely … he could draw, paint. He could mend things. He made the children lorry carts and cots and farm yards and things like that. He was like a hands-on house person. His first dad, if he’d lived, they would have been kicking a ball and climbing trees and things like that. So you don’t know how it would work out, do you?

I mean, we’d got problems. I don’t know whether I should be telling you this or not. We exchanged the prefab for a three bedroom council house. They wanted to downsize and we had had one more child, which was a female, so we had a boy and a girl. And I found out I was pregnant with another baby, and they wanted a smaller one, we wanted a bigger one, so we exchanged. I’d got it into my mind I wanted to buy my own house, not live in a rented property. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the time for moving, but you don’t know that at the time. And we moved from Almondbury, to a house in Meltham. With hindsight, I should have let him go on two buses to school every day and two buses home, but I thought if we moved him … And he was 14, funny age. He would meet boys his own age, and it didn’t really work out. He played truant because he was unhappy at school. It was a school where he didn’t know anybody. It was not a good period. It sort of affected his life from then on, because instead of finding his own age which he’d gone to school with since he was five, when he left school, you had no problem getting a job in those days. His first job didn’t work out. He was going to be a green keeper. And he ended up working in a mill. He worked with married men, and so his going out in the evenings seemed to consist of going to a pub with these men that were married, not to nightclubs and that with younger men.

So, unfortunately, he met someone that was already married. And they didn’t … She had two children, but they never had any children of their own. So, we can’t alter the past. My daughter, the one in Surrey, was going to move. She was coming back with her three children and she said, “If we don’t do it before she starts secondary school, we can’t do it at all.” It was working out. She’d got her [farm-style cottage] to rent empty. She got the three children in a school near Holmfirth and suddenly the man that was buying their bungalow pulled out. Her husband became redundant and it all fell through and since then she’s still down there. So, she didn’t do it but, it didn’t work out. But we don’t know these things, do we? It’s nice to own your own property, but at what cost?

Well you did what you thought best at the time.

Yes, and looking back, I try not to be bitter, but I am a little bit because it was National Service, and nowadays they bring the bodies back and they make sure the widows are well looked after. And you just feel as if you are just kicked into touch, so to speak. But if I hadn’t met my second husband … I’ve had two wonderful daughters who are a joy and a blessing. So I’ve got my son who was dearly loved, who is dearly loved, and I’ve got two daughters that have produced children, whose children have produced great grandchildren who are a joy to me. So life, life has been good. It’s been different, but it’s been good.

So you have a relatively big family, some of them further away than others.

Yes. Elaine has lived in Surrey since she was about 23. They have to go where the work is. She came back from America after almost a year in America and she couldn’t get a job. She couldn’t have any money from the State so she had no money to live on. And, she went down south and stayed with a girl she’d met in America and within a week she’d got a job. She’d got a flat in Wimbledon and she’s been down ever since. So, she’s more Southern than she is a Yorkshire lass, but yes … So, she’s produced two girls and a boy. And my other daughter, who lives a couple of miles away, she has three boys and they have now three wives and, and we have great grandchildren now. So … Yes, it’s nice to have a family that include you. This is what I’ve always said: families come first. It isn’t easy. It doesn’t happen without you working at it. I am included in lovely meals and peoples’ get together and I appreciate that. And they make sure I’m alright, if I need anything doing. So I live in a nice part of Meltham in a bungalow that is easy to look after. And up to now, I’m getting back to being self-sufficient, so we’ll see what life throws at us.

How did it feel when you met your second husband? You said that you had the blessing from your first husband’s…

Family, yes. Yes I did, yes because I used to see them weekly. They were very involved in their grandchild. I mean they had to come to terms with losing their son, which is hard. Because when he came, I think it was the first time I’d met his dad after the news and he just said, “Well, lass, that shell add his name on.” And, you know, they just … well … you have to accept it. It’s hard when there’s no grave to visit or, or anything. It’s still, still hard but it used to amuse me in a way because his mum was so, how can I put this, she was lovely. I’d go months without seeing her and she’d never once say, “Where have you been?” She’d welcome me and that. She got into an impression – an impression of life as a soldier – that he was in a little sentry box in Korea being a soldier. She could never come to terms with what I found out when I went over there was happening. It was horrendous what I heard, it was horrendous. And, she just thought he’s in the Army, Buckingham Palace, a soldier in a sentry box [laughs] and, in effect, I’ve heard since that … I mean, there’s people that never had a body to go and visit in Korea.

Their names are all up on these things. And, I heard that when they were captured to take them one from place to – it’s only hearsay – one place to another, they used to shoot them through and then pass a chain or something, or a rope or something through there, and pull them along all in a line like that. But it’s hearsay. But it is true that they were taught to fight on the ship going over, so there’s none of this being trained like they are for these modern wars. So that has … I haven’t been able to come to terms with that.

What was the effect on you not being able to have a funeral?

Well, my biggest priority was that I didn’t fall to pieces, because I was pregnant and I was at a difficult stage of pregnancy. So I had to really not get too emotional because it would have harmed the child, wouldn’t it? But it is hard when you’re trying to bring a child up now, then, in those days, because I can remember being worried about him at one stage and taking him to the local clinic, which is now no longer there, and being sort of accused of being highly strung. You know, “You’re worrying unnecessarily. There’s nothing wrong with your child,” and sent on my bike again so to speak and then having an apology because they’d looked at my record or what and suddenly realised I was a widow, and only me to look after this tiny baby, responsible for one. Then when I did remarry, people can be hurtful.

I had some hurtful things said when I was on my way to the nursery with him, by people stood in a queue and assumed that you were going out for pocket money and things like that, and you’re actually going out to pay the rent. You let it go because if you told them why you’re there … And so … I’ve forgotten what I was going to tell you.

People would say some hurtful things … ?

Well, I was in labour and this nurse came to the bed. Or was it after she’d been born? “What have you been doing for five years?” said she, because there was five years between my son [and daughter]. I said, “Well, as a matter of fact, I was widowed.” You know, they’re so flippant sometimes and so judgemental. She was an Irish lady and as far as they were concerned there was no such thing as contraception in those days. So that more or less … “What did you want me to be doing?” People assume, if they see somebody with one child, “Oh, you’ve only one child.” That person could have lost a child, which happens. I know, I know someone, and it would have been so easy for me to say, “Oh, only one child.” She’d had a child and that child had died. So you have to be careful what you say to people.

What were people like with you?

Well, to start with, they don’t like speaking to you. It’s the same now. If you lose someone, they don’t know what to say. And you get yourself pointed out. I got off the bus and, of course, I’m out here [heavily pregnant], which it didn’t say in the paper. There was no big article. It was just in death column. I’d taken that down myself. I got off this bus, and I saw these three turn round and point to me. So, they – wherever they lived further up – they must have said, “There’s somebody further down that’s been widowed,” and suddenly they look at you: “You’re pregnant.” So they don’t really know how to treat you. And it isn’t that they’re being cold or anything. It’s just they don’t know how to treat you. I’ve seen people cross over the road sooner than come up to you. Then I took my son – I think he would be about two – and I took him to see a friend that had moved down south, on the train. This lady – it was when they had compartments and you sat opposite each other – and they were smiling at him and said something about his daddy.

So I just said, “Well, I’m sorry, but …”, and then I just told a brief version, “You have upset me,” she said. I thought, “You asked. What do you want me to say, that he’s got a daddy? He hasn’t got a daddy.” You know, and so, it either – how can I put this? – I don’t want to make it sound bitter. I don’t. I’ve said that before. It makes you strong. You either go under, or you start swimming and you survive, and I survived. So on the whole, I was self-supporting because I’m that sort of a person. I mean they got dysentery at the nursery, so I couldn’t take him there. He didn’t, but the nursery had it, so you couldn’t take your children. So that meant no wage coming in. So you just did the best you can. That Christmas there was no presents for … You know? So, you managed the best way you can. You pay your bills as you go along.

So, when we got married, my husband moved into the prefab, which I don’t think his sister-in-law ever forgave him for because he hadn’t had to provide a home. You see, he moved into a readymade home. And he, like I said, he could make things. I mean that table … He made that table out of … It’s nothing posh, but every time I look at it, I think, “Peter made that.” So, you know, somebody had said to me one day, “Is it a question of love?” My love [for] my child? and I thought … To start with, I thought, “That’s a silly thing to say.” And then I thought, “It’s a truthful thing to say.” Did I marry him because I wanted a father for my child? You know, so … But like I said, I’ve got the son and I’ve got two daughters, so I consider myself extremely lucky.

These days, finally, and it’s not been very long, war widows don’t lose their pension anymore when they remarry.

No, I understand so …

What do you think about that? Because of course you lost yours …

Yes, I did. It would be so easy to say … I don’t know. Its … [Pause] Part of me thinks you’ve got a new life and that’s part of your old life, but I have – I can say this, can’t I? – I was told years ago by somebody whose husband died as a result of the injuries that he got during the war, much to my amazement, it all depends what it says on their death certificate. She has got … Bless her, she’s dead now herself. She got the war widows’ pension. So I kept – I didn’t tell my husband these thoughts I was having because he had quite a lot wrong with him over the years – I kept that in mind. So when my husband died, which will be four years in February, without a great deal of fuss, I put the wheels in motion to apply for it. There was no problem with that because, with me already having had it, it wasn’t something new I was going to get. I have [it] now instead of the state pension.

It isn’t a lot more, but it is. You don’t tax it – it’s tax free, so that is a big thing. So, it was like, it was reinstated. I’d stopped having it, and now I’m having it. So I suppose as well, my age, perhaps they think they wouldn’t be paying it very long. [Laughs]

You are still a war widow, aren’t you?

Oh yes, yes. And, I haven’t changed my name back, but I think possibly because I remarried they didn’t keep in touch because I had a different surname then. But I wasn’t kept informed of anything I was eligible for. Perhaps you don’t remember but a few years ago, I don’t know how many years ago – about four – the Queen Elizabeth Cross. Now, I have one in the bedroom. It was my son-in-law that told me about it, and it was for people that have lost someone after World War II. He said, “You’re entitled to it,” and a beautiful thing it is. I could either have it sent through the post, or I could go and have it handed over in a service, [and] I chose the latter. We went to some barracks in Leeds. And, the Lord Lieutenant, who is a lady, very nice lady, she presented them. There were widows there from the Irish thing, and there were widows from Afghanistan, and they were like … It was a varied age group of people. Some of them were deeply upset and she thought, you know, I was calm.

I mean, we’re talking 65 years now! I mean, this would be four or five years ago. I can show you it if you’ve never seen one. But that was a very moving service, yes. She was very interested, she said she would like to speak to me again, but by the time she’d finished shaking everybody’s hand and somebody said to her, “Your next appointment is …”, she was off. She was really interested because I was a widow. It’s a long time. I’ve had to build my life, you know. I mean, we weren’t married all that long before he was whisked away. And we thought he would come back and we would, you know, … And thankfully a lot of people did. Is there any way that you could tell me of anybody that’s in my circumstances that are anywhere within accessible [distance] … ?

We can try.

I know there was a lady. She was a widow, and I would have been better going with her to Korea, but she has died. I do know that. But I just wondered, you know, because there won’t be many of us still alive, you see, will there? Because it’s 65 years since he was killed and he was killed in the May. The war was over in the July. So … But I’m pleased I went to Korea.

Can you tell me some more about this? I know we spoke about it before we started the interview. When did you go? What made you decide to go?

Well, I think I must have read somewhere the Government were paying for widows … They didn’t pay for your children, or they didn’t pay for the mothers and fathers, but they paid for the widows. So I applied and I was granted permission to go for £10, and Peter could go with me, but we had to pay the full fare for him. So, the British Legion arranged it all and wanted to know your medical details, whether you were capable of going or needed a wheelchair or you needed, you had some disability where you needed … And they took someone medical that made sure you were alright the whole time that you were there. You couldn’t have been treated better if we were royalty. So we flew from Heathrow to Korea and then we flew down to Pusan and saw the grave … The graveyard, which is as they are in every country, beautifully kept.

And, I did send, a few years ago, Roy’s photograph (my daughter said you wouldn’t need all these on this visit. I would have got them out for you if I could have found them). And so, they wanted anybody that had had anything to do with the war. Would they send a photograph to somebody in England? And they did. What they do is they’ve got these records in this beautiful little purpose-built church-come-room. Lovely service it was. And, every day, I think it is every day, someone’s photograph is taken out and put on display. “This man gave his life for us,” you know. So they got a lovely photograph of Roy. It is a nice one. So, they know all about them: how old they were, and everything, which is nice. So, you know, the other side of the world, they’ve got a photograph of someone that’s given their life for them. So every day … We went down especially for this service and found the graves and paid your respects and had a service outside and that.[1]

And then we were taken by coach back to Seoul, and we were shown various spots that were relevant to the war where the Duke of Gloucester lost a lot of men. Always it was raining, and when they were playing the bugle and the Last Post, those poor men were stood there in the pouring rain. And we were treated with nothing but respect. We were taken to the … What did they call the chappy that’s from England that lives out there? Er, you know, some dignitary that …

The ambassador?

Yes. And we were treated to an En- … which was nice … an English meal. And that was nice. But it was really, laughable really, because the first place we pulled out – up at, we went in this, I suppose the equivalent of a restaurant or something like that –and my husband, bearing in mind he was 6ft tall, or 6ft 2, walked with a stick, had a knee he couldn’t bend, and they were little tables, no more than 8 inches off the floor and you’re supposed to sit on the floor and have something to eat off this little table. Well that was out of the question. I mean you’re talking about people that were older, you see, so they had to find some chairs for us to sit on. I think it’s the only holiday we’ve – ‘holiday’, it was a pilgrimage – that my husband and I have lost weight on [laughs]. ‘Cause we, we don’t eat foreign food. And, you know, there was seaweed soup and things we’d never heard of and neither of us are, him worse than me, adventurous into trying anything new.

So we were glad when we went somewhere like a burger bar where you knew what you were eating. And, so it was a real eye opener. A different culture, isn’t it? So everywhere we went, there were the names of the fallen. And so we were treated special all the way through. Beautiful hotels we stayed in, taken to see various, you know, palaces and things like that, but it rained, and it rained, and it rained.

Not unlike in England.

But the day that we were flying back, the sun shone. Must have said, “They’re going now.”

How did it make you feel to be able to go to Korea and see the grave?

I was upset at being told what they’d had to put up with because we’re so blasé. “It’s happening over there, I’m not involved.” But you found out why the war had started. We went in a coach over the border to the parallel line.[2] There is this hut so to speak. And when we were, we had to pull up at the side of the road and these armed, Army people, grim face, and we’d been warned that we had not to have eye-to-eye contact with them when we were there. We had – no way we had to talk to them. And we had to only take photographs when told we could. So they came in, they wanted to look at everybody’s passport before the coach could go any further. And so we were told what to expect. So we duly got out and were taken past all these guards to this place and there’s this room where they never actually signed anything.

I don’t know whether you know that or not but the war has never actually been signed. One half was the Koreans’ and one half was the Americans’. A lot of Americans died in that war. We were actually stood at this table where this went on. So that was divided. Then we went into another room and watched a film show and was told … I mean when you think about it, if you’ve ever seen a map of Seoul, its a little tiny corner and Korea, North Korea is huge. It pushed, pushed them back right to Seoul, hadn’t they? Then the Americans stepped in, you see, and we started surging forward. [MacArthur],[3] he wanted to drop the Hiroshima … the nuclear bomb … on them. He was trigger happy. He was ready for … And the war would have been over two years sooner except for him. Instead of being satisfied of pushing them back, because the Chinese had come into it then.

They were fighting for the North Koreans. So they pushed the Chinese back and they got within, like, twenty miles of the Chinese border, and he wasn’t content. He wanted to push them back further. So the mass invasion of the Chinese, who were not bothered about killing themselves … It’s a glory to die … They started this massive surge, and the death toll then was horrendous. So I was told where Roy had been killed. Apparently, there was this noise that came out of the trees, constant bombardment to their ears, of music and trying to brainwash them into how rubbish the Americans and the British and the fighters were, and how good they were. Well, can you imagine that, trying to sleep at night when you’ve got all that going on? And, I mean they were inadequately armed with what the Chinese had produced you see, but in the end, as you know, they did push them back, but he was pushing them too far, so the war ended.

I mean, it’s such a tiny, tiny little place. But it’s a … I mean, we didn’t get to do a lot of sightseeing like that. We were taken places mainly because it was a pilgrimage. But Peter was sort of resting because he had a lot of problems, and I was out walking by myself, you know. There’d be street after street of shops selling the same things. A street full of bridal wear, a street full of men’s wear, a street full … you name it, they were there. It’s not like ours where you have a draper’s, and a … It was absolutely amazing, yeah. So, yeah, it was a pilgrimage. But I did see a little bit of it because I did venture out on my own, but if you didn’t go down for breakfast at a certain time, it was all cleared away. There was none of this “it’s between certain hours”. So you had to eat what you can of what they offered. And, it’s totally different, you know. We’re used to being catered for, aren’t we? [Laughs] I’m glad I went, but it’s just I didn’t feel that I’d been able to release anything. But we went and I did see his grave. I did have some photos taken.

That was another thing because we’re not up on anything like that. This camera … [We] didn’t check that it had a battery that was working, and so to start with we couldn’t take any photographs at the cemetery because my camera wasn’t working, but we managed to find a little shop that sold me some batteries, so … And somebody kindly sent me some through the post so that was alright. So I took a photograph of his grave. So, we got talking to somebody who was visiting … Was it her brother’s grave? It might have been. An older brother or something. And, they were nearly the same age because my husband was 21 and I think some of those, you know, could have been 19, 20, 21. And I just got friendly with this young lady. She just said … Well, I think I might have said it to her, “Perhaps they were friend.” With them being of an age, you know, they might have been friends. But some of ‘em were visiting their uncles, you see, but I think it was her brother. But one lady hadn’t got a grave to go to because they’d never found her uncle’s body.

But one half of the cemetery was completely empty because the Americans had taken every one of their dead home. They also paid for all the relatives of whoever had lost their life to go and see, whereas our county restricted it to paying for the widows, so … Anyway, I’m glad I went.

You said you felt a little guilty when you … whilst your second husband was poorly and in a home, and you were trying to arrange to finally have Roy’s name …

Yes.

… commemorated. How did you feel when Peter came on the pilgrimage?

Well this would be at least, I think it was about 2000 when I went, so we’d both be a lot younger. But he wasn’t a man that asked you questions or talked about things, you know, so this is probably why I didn’t explore things sooner because he was my husband. But I think when we were first married, sort of, not have nightmares, but start dreaming during the night. I dreamt that he hadn’t died and that I had to choose between them and things like that. It can be upsetting because you’ve left one life behind, but it’s still with you. So, you’ve got to adjust to realising that it isn’t going to happen. I mean, it is a big thing to take on somebody with a child, isn’t it? I mean they do it now all the time, don’t they, but they didn’t in those days. People brought up children on their own. So, I mean I was married to Roy in 1951 and he was killed in ’53.

And, he’d been away from the November when he went and caught this ship, and killed in the May, so he’d been abroad six months. I’d been working and leading a life, and he was the other side of the world, so I’d already started living my life on my own, as it was. And then, you see, and then I was married to Peter for … I was 26 when I married Peter. So, I mean, we’d been married nearly 58 years when he died. So, I’d had a lot longer with Peter than I’d had … I’ve lived my life with Peter, haven’t I? So, you’ve got a life and you live it the best way that you can. But it certainly was something that I had made my mind up was going to happen because nowhere was his name. Then suddenly he’d been instrumental in that. He was under the ones for the First World War, I think, and it was just a thing. So, every Armistice Day after that I went to that church. They had his photograph on one of these things they project, which was lovely. So yeah. Yes, I did get closure, I suppose, in a way. Yes. Yes.

Kathleen, we’re talking on the 13th November, just after Remembrance Sunday and Armistice Day. What did you do last weekend? Do you normally mark Remembrance?

Yes. When that happened, I went to this church the other side of here but then … I don’t know how I can say this. It’s in a poor part of Huddersfield, money wise and property wise. And the church welcomed me very much so, and each year they were pleased to see me again and made a fuss of me, and my husband’s name was read out. But the one in the village is a richer church. And it’s more pomp with it. So we get the brass band marching through the streets with the people following it, the Brownies, the Guides, the Scouts, firemen. So we’ve got all that, and the church was so full this year. I’ve never seen as many people that there wasn’t room. They were down each side, they were in the back, they were upstairs. Those at the back couldn’t have a sheet because they’d run out at the service so they were listening to the hymns but couldn’t sing them.

It was absolutely … You see, it’s been so publicised this year with it being a special one, hasn’t it? I’m always deeply moved when I go. But for just one year I asked for his name, but there were people that had lived in Meltham they were reading out, and people that had died in the First World War. And I was quite happy for my husband’s name to be read out where he’d lived. So, it was a very moving service, yes. So, you see, you get your flag bearers taking the flags down, then the poppies with the wreaths, they carry those down. Well, we didn’t get much of that at Moldgreen, although it was a service and it was very nice, it just didn’t have that feel. So I’ve come back to Meltham, and I did go to it, yes. I wore my medals. I don’t wear the big ones ‘cause I have only three. They’re heavy. I have had some miniatures made and I pin those to my coat.

What does it mean to you, Remembrance? Is it important to you?

The?

Remembrance.

Oh, the remembrance? Well the first or second year it got to me and I felt I had to speak to the vicar. I met her at a later date on the street, and I said to her, “Excuse me, but in your service on Sunday, you never once mentioned Korea.” I said, “It’s the Forgotten War.” It’s known as the Forgotten War. I said, “But my husband gave his life. He’s buried in Korea,” and since then, that is added to all these extra places where people have given their lives now, whereas as far as some people are concerned, there’s just been two wars, the First World War and the Second World War. I mean the Second World War, I was eight when it broke out and I was 14, I’d just started my first job when they announced that war was over. So I’ve been through the hard times in the Second World War. We weren’t bombed much at all in Huddersfield, but there were shortages of people being able to buy things. So, there was no obesity in the war years because there wasn’t the food to indulge. So, you just managed with what you could get … improvised.

So yes, it’s something that happened to me and I don’t want to think that people are going down that road, which they’re not now, no. But people are losing their husbands. I mean even, some people are being killed not necessarily by the enemy but by somebody, you know, in the Army firing a gun and somebody has dropped down dead. And people have lost their lives, haven’t they? It’s always tragic when they’ve served abroad and they come back and get killed in a car crash or something like that. But, I mean, people are dying and people are losing their husbands or their wives. Wives as well, yeah. There’s always some tragedy and I always relate to it when they say, “You don’t know how I feel.” “Yes, I do know how you feel, yes.” So …

You’ve got to be strong to survive, and you’ve got to manage, accept help, yes. But on the whole it was down to me. I mean the British Legion had been very good, but with marrying again, I think I only once ever asked them for help, and it was because it was a cold winter and my little boy hadn’t got a decent coat. It was the first time that I had asked for help and they sent me some money to buy one, so I bought him this little coat. But with remarrying, you see, it was more or less me that kept in touch with them. But over the years, to start with, they wrote and asked for money because, you won’t realise, there wasn’t a memorial in St Paul’s for the Korean War. And so they asked people that they knew were connected with the Korean War, would we send some money to pay for … and there’s no names on it. There’s only regiments all the way. It’s not very big, not very big. And there’s all names, Duke of Wellingtons and all these around, but there is no names.

You go down to the Afghanistan one … wonderful memorial with all their names. So, they’ve asked for money over the years. They used to, on Remembrance Sunday, send you a cross and you were expected to send some money back. And you wrote a message on this cross, and they put it … I think it was in St Margaret’s gardens or something. And they did, for a few years, quite a few years, they sent me an invitation. But going from here down there for a service and to see all these crosses, it was out of the question. So I used to send a cross and then they stopped doing that. They said, “They would put a cross for you in St Mary’s.” I think it’s St Mary’s. But then I started doing it local so you don’t need something like that, you remember every day, whether it’s six months, six years, 65 years, you still remember.

Why do you think people still forget about war widows? The reason we’re talking to you today is that people don’t really know what wives face when their husbands lose …

No, no they don’t. No. Well, I feel differently about it because it’s always hurt more because he didn’t want to go in the Army. And they could either finish their apprenticeship and go in, or go in and come back to it. But nowadays, I heard one lady saying about her son and he was bored with life and he wanted a bit of excitement, so he joined up. Now, you see, they go, and they trained because now there’s a war and the wars are getting more fierce, aren’t they? There’s these bombs that can home in on somebody and chase somebody, so they’re going to be different things. But my husband, with his National Service, was taught how to square bash. Then suddenly he’s sent to war. Now they joined knowing that there were these wars on up and down, they could be sent abroad. They go abroad now with mobile phones. They must keep the money for them in this country, keep on feeding it for their phones to … My husband sent me letters that were badly censored, “Oh. You can’t say that.”

So somebody has read every letter that they send you, everything that it says, and now you see they’re talking to each other. “He’s been away five months.” Well, during the other war they were away five or six years, weren’t they? I mean, my husband, I didn’t know when I was going to see him again. I mean, I think he came home after he’d finished his training, and then he came home because they were sending him abroad, and that was it. But I don’t know what to say to that because, I mean, nowadays there’s such a lot of money they’re given and the pensions will be more, more money and they bring the bodies back. They always arrange an official military funeral, don’t they? I mean there’s a young man in Meltham, and they’ve raised a lot of money, and there’s seats at various places with his name on. I’m not against that, but he joined the Army because he wanted to be a soldier and fight. My husband joined the Army because they made him go. So, to me, there’s nothing the same there. They go and they’re paid to fight.

My husband was going to do what he needed to do because they said so and didn’t come back. So it’s still sort of … He’s there, when they’re saying about where they were killed. Well yes, but they joined up. My husband was, you know, dragged in. So I suppose, in a way, it’s just something that happened in those days, isn’t it? I mean I’ve spoken to people and their husband’s have come back safely because they’ve been doing nothing to do with fighting. Yeah. I was deeply upset a while back because I belong to a women’s fellowship. This man was talking about Korea and, unfortunately, I was in this, in the audience so to speak. He started laughing and joking, and I nearly got up and walked out. And I did say something to him because he said, “I don’t suppose anybody has been,” and I said, “Well, I have been to Korea, as a matter of fact.” I said, “My husband is buried there.”

And he was making jovial of what had happened while he was there. They’d done this, and they’d done that. And he was trying to make his talk as interesting as possible to all these ladies that were there, but it hurt me that my outcome of my husband going and him going was a different thing altogether. So, some people can’t comprehend what it means. [Pause.] But I’m still here. [Laughs.] I think the biggest insult of all, though, is the government having the audacity to add 25 pence, isn’t it, to your pension when you get to 80. [Laughs.] It doesn’t even buy a postage stamp. They should stop it.

Kathleen, what is it … If there was one thing that you wish people knew about war widows, about wives who’ve lost their husbands to their service in the Armed Forces, what would it be?

I don’t think I can answer that. I mean it’s just a question of … When it’s happened to you, you need family around you to support you when you need it. It’s just survival of … Nothing ever goes away. You never get over anything. You learn to live with it. If people, if you were down, which after 65 years, it’s a different ballgame … You just need somebody to be there if you need ‘em or put their arm around you and say, “Are you alright?” You don’t want material things, no. I mean I could have done with a lot of material things when it happened to me, but that was then, and this is now. So people have got a different standard of living, haven’t they? Yeah. [Pause.] So I just dug my heels in, did what had to be done each day, and got through, but I’m blessed with a family that care for me, include me. That’s most important, to be included.

I think you’re still swimming in one form or another.

Hopefully, yes. After my fall, which, unfortunately for me, the elements were against me and things didn’t go like the doctors thought they should. So after plastic surgery, which was a wonderful job, I’m trying to come to terms with what I can do and what I will never be doing again. I will certainly not be kneeling down again [laughs], but I’m determined. I think that it helped me because I’d been going to aqua fit for 26 years, twice a week, sometimes three times a week, and I’m sure that that keeps you supple and stops ageing, I suppose, to a certain extent, or you feel ageing. And it does you nothing but good physically. But I don’t want to be treated as if I’m disabled, you know, and I need special treatment. I don’t want special treatment. I just want to be able to safely, at no worry to others, jump up and down a bit and see how high I can jump, if I can ever jump again. There are certain strokes that I will not be able to do because of my knee.

I’ve never let my granddaughter forget what she said to me because she works in a hospital, although she’s enjoying herself just now. She’s in Australia. She’s gone for three months to Australia and New Zealand, then going to Fiji, is it? She works amongst this technology, with machines and x-rays and that. She said, “Grandma, of all things, it’s better for you to have done your patella than your hip or your …”. Well I’ve not let her forget that because everything went wrong. [Laughs] So, it didn’t turn out straightforward, but I’m doing what they told me to do, and I’m hoping to improve my mobility and not be a worry to people. I can’t climb steps no more to put things up, like the step ladder, not steps in a shop or a bus. So you’ve got to come to terms with no, you don’t stand on that buffet. No, you don’t carry too many things at once and so I’ve had to take a backwards step and ask people to do things that normally I would do myself.

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about, Kathleen? Anything that we’ve not covered? Anything that you’d like?

No, I don’t think so, no. I get through life by reading the paper, doing an easy crossword, not the hard ones. I like knitting, so I’ve knitted scarecrows, octopuses, hearts, Christmas pudding hats. I must have knitted at least 40 of those for people. And so, to fill your life when you’re older you need hobbies, and you need to feel useful. I like baking, but it’s all given away. Coffee mornings, family, friends, so … . I like to be independent. So that’s what I’m aiming for.

[End of Recording]

[1] Respondent Clarification: Kathleen attended one service while on her visit, but the services are held daily.

[2] Clarification: Kathleen refers to the fact that a fellow passenger on the coach had informed her that prisoners of war were shot through the hand and joined together with a rope so that they could not escape.

[3] General Douglas MacArthur, who led the United Nations Command during the Korean War until April 1951.

Very proud to say that Kathleen is my mother-in-law. She is a magnificent lady with an extended family who all love her to bits. She recently has recovered from a fall on cobbles that resulted in a broken patella . She has worked like a trojan to regain her mobility and is now walking and driving again. Indomitable is a word that describes her very well.

As a young Mum she had a tough time in 1953 when she lost her husband Roy in Korea. Things got better when she remarried and added to her family with her second husband Peter – a lovely feller who supported her in everything she did and went with her to Korea.

They don’t make ’em like Kathleen any more!!