By Steve Murdoch and Kathrin Zickermann

Steve Murdoch is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of St Andrews and Kathrin Zickermann is Lecturer in History at the University of the Highlands and Islands. Together, they research the roles of women in the Thirty Years’ War through the lives of the widows this conflict created. In doing so, they reveal the complex combinations of formal and informal support structures on which these women could rely. They contrast the Scottish experience at all ranks with those of women in Sweden and the Dutch Republic and show that, far from being the “beggars” with whom they were often equated, the widows of the Thirty Years’ War could be resilient and successful, worthy of study in their own right. You can explore Steve and Kathrin’s research online via the Scotland, Scandinavia and Northern European Database.

The role of Scottish officers and soldiers during the Thirty Years’ War has received considerable scholarly attention in the last two decades. Some 50,000 of them served in the anti-Habsburg alliance alone. It is a sobering point that the vast majority of these men, whether generals or private soldiers, lost their lives during service.

Our research has not been without problems, not least in the identification of the women themselves. Some 8,000 British and Irish individuals who migrated to early modern Northern Europe have been identified with fewer than 400 of these being women. For the majority, the entry is simply a fleeting reference from a church or baptismal record. However, it has been possible to tease out more information on over 100 women who became widows during the Thirty Years’ War. For some remarriage was an option available to them after an appropriate period of mourning, usually a year. For others, years spent petitioning the authorities for compensation, pensions or other means of support was their only option. For the moment we have targeted those located in the Dutch and Swedish armies to consider the problems the widows faced upon the deaths of their husbands in foreign service.

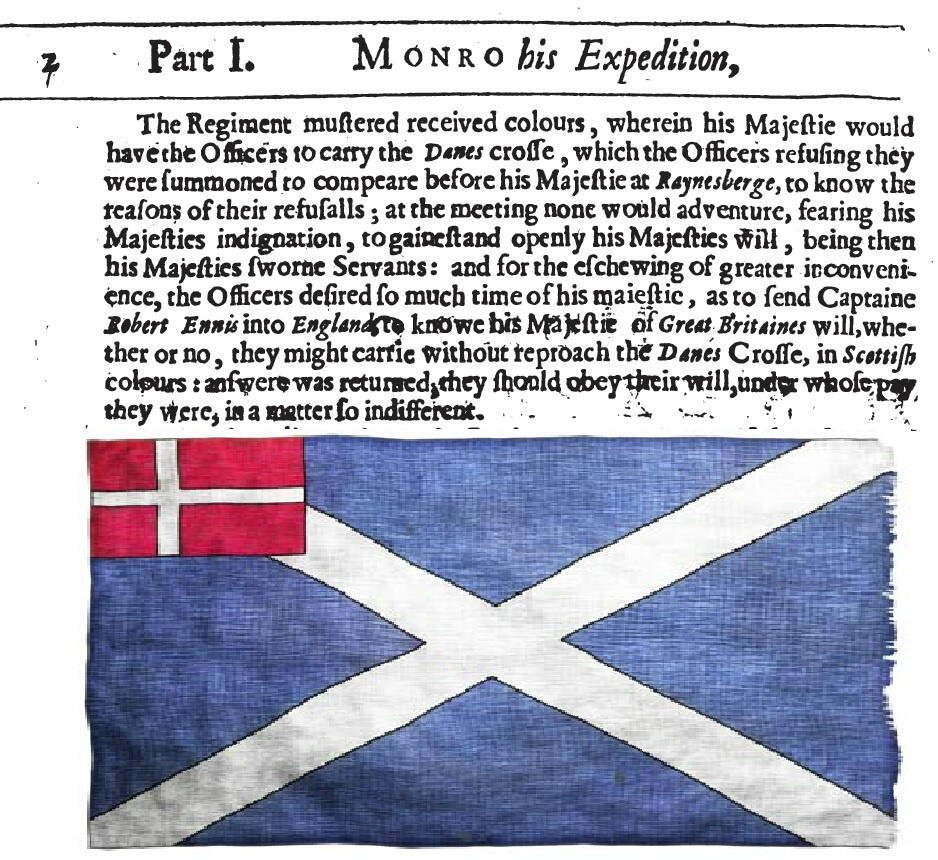

The colours of the Scottish army in Denmark 1627-1629. Granted by Charles I after the men refused to fight under foreign flag.

James Ferguson long ago collated the archives relating to the Scots Brigade who served in the Dutch Republic during the period, and these include valuable records for wives, widows and children. Scottish women in a Swedish context have proved harder to identify. Their correspondence is seldom catalogued under their own name, but rather under those of the men in their lives, often their late husbands, but sometimes their sons. To find the illusive ‘widow letters’ you must first know the name of a soldier who was married, who died in Swedish service and whose wife then wrote to the Swedish authorities claiming a pension or similar entitlement. Nevertheless, a valuable corpus has now been collected, digitally photographed, and the process of transcribing and translating it is well under way.

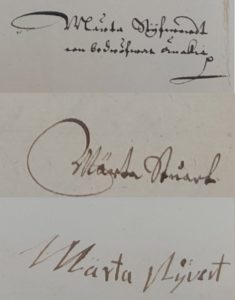

Signatures from the letters of Martha Stuart suggest that she was illiterate and the letters were written by notaries or scribes

The women from various ranks in society were mostly literate, though many letters were composed in scribal hand as evidenced in the numerous signatures of one of our most prolific ‘writers’, Martha Stuart. The languages they used, just within a Swedish context, includes Scots, Latin, Swedish and German with several of them seemingly shifting seamlessly between each. Our Dutch-based widows used both Scots and Dutch, though always the latter for in Wills and Testaments.

Signature of Cicilia Spens. Beneath it reads in Swedish “The late Major

General David Drummond’s wife and surviving widow”. Her letters are filed under his name

It is not surprising that Scottish soldiers sought to provide for their wives and children after their death, particularly given the nature of their profession. One ‘Leendert’ Graham, a common soldier, made a joint will with his wife Christina Bruce in December 1635. Both were named as sole beneficiaries in the event of the other’s death. However, the cases of children inheriting instead of their widows is not uncommon. Trumpeter John Maxwell specified that his wife Jannet would become his beneficiary, but only if he died childless. Others had a different view, such as musketeer David ‘Vloeker’. He stipulated that his children could inherit, but only after his wife had died. In the higher ranks Major General James Ramsay used his will to urge his wife Isobel Spens to remarry someone from an established family for the sake of their child. Nevertheless, despite the care taken to ensure the security of a widow, their ability to retrieve an inheritance or pension were precarious at best.

Some provision was available from the Dutch Council of War for the widows and children of officers. However, there was no consistency in what was granted. In 1621 four Scottish widows received Dutch ‘life pensions’, albeit the amounts received varied. The widow of Captain John Balfour obtained an annual payment of 50 guilders, whilst the widow of Lieutenant Colonel Calvart (Barbara Bruce) and the widow of Captain Strachan (Anna Kirkpatrick) received 200 guilders each highlighting that rank was not the defining factor for the amount awarded. Rather, it could come down to length of service, or in some cases, special awards based on the bravery of the soldier.

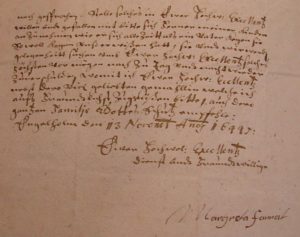

Letter from Margaret Forrat (wife of the late James Spens)

Almost all pensions applied for by widows of officers in Dutch service had been granted prior to 1620. The following year the States General declined the application for a pension from Delia Butler, widow of Captain David Ramsay, but instead awarded her 80 guilders to facilitate her return to Scotland where it was known that her home parish would have responsibility for her maintenance. It’s noticeable that this reluctance to pay pensions was exacerbated by the end of the Twelve Years’ Truce between the Dutch and the Spanish (1609-1621) particularly after the siege of Bergen-Op-Zoom in 1622. There were now many new widows for the Dutch to deal with. Some, like Christina Boswell, pursued the Dutch authorities for over a decade before winning her case.

With institutional support sporadic at best, many widows used alternative strategies. Many cashed in their social capital with individuals at the highest level of the military leadership or with requests made directly to the government concerned. Isobel Spens directly petitioned the Swedish Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, for reimbursement of her pension rights after General Ramsay’s death. In order to enforce her claim Isobel emigrated from Scotland to Sweden in the mid-1640s without knowing a word of the language. Her relocation proved successful and in 1647 her son David was awarded various estates in Sweden, but on the condition that Isobel would hold them in her possession until her own demise. In 1649 Colonel William Forbes interceded on behalf of Isobel Forbes, who had lost her husband several years previously. Widow Forbes’ own financial burdens were increased by the responsibility she had for the children of another Scot whose wife had been killed in the war. There had been some financial support, but this had ended abruptly. Thus she called on her kinsman, William Forbes, for help and he in turn took her case further up the extended kinship hierarchy to General Alexander Forbes in order that her remuneration would be reinstated.

These few cases only give a flavour of what we have unearthed to date and we look forward to revealing more as the project progresses. There is certainly more to come.

Kinda makes one a fulltime pacifist.

Indeed 🙂